Planning is one of the fundamentals of modern life. We all practice it to a greater or lesser extent. In our personal lives we plan holidays, careers, the acquisition of assets (e.g. cars, consumer goods, houses); sometimes we do detailed planning with budgets, on other occasions we do it fairly informally, simply 'work things out in our heads'. But however we do it, planning, essentially, is the 'organisation of a series of actions to achieve a specified outcome'.

In work environments, where we typically refer to it as 'business planning', we adopt a generally much more systematic, disciplined approach. We plan projects, plan and develop new products and services, new initiatives and programmes. We also draw up plans for change, for doing things differently, doing things better. We also discuss, draft and then implement short, medium and longer-term plans as to where, organisationally, we want to get to, what we want to achieve.

In essence such plans are organisational 'route maps' to get us from 'where we are at now' to 'where we want to get to' at some defined point, or points, in the future.

They are also the essence of what, today, we call strategic planning, something that has, since the early 1960s, grown steadily to become one of the essentials of modern business and organisational life.

Planning in Business Environments

Management theorist Henri Fayol (1841-1925) whose work still endures today (see section 5c) included planning amongst what he said were the prime responsibilities of management:

- planning

- organising

- command

- co-ordination

- control

He described planning as: 'examining the future, deciding what needs to be done and developing a plan of action'.

Strategic Planning: Definition

“Strategic planning helps determine the direction and scope of an organisation over the long term, matching its resources to its changing environment and, in particular, its markets, customers and clients, so as to meet stakeholder expectations.“ Johnson and Scholes, 1993

Strategic Planning: What is it?

Strategic planning is a systematic process of envisioning a desired future, and translating this vision into broadly defined goals or objectives and a sequence of steps to achieve them. In contrast to long-term planning (which begins withthe current status and lays down a path to meet estimated future needs), strategic planning begins with the desired-end and works backward to the current status. At every stage of long-range planning the planner asks, "What must be done here to reach the next (higher) stage?” At every stage of strategic-planning the planner asks, "What must be done at the previous (lower) stage to reach here?” Also, in contrast to tactical planning (which focuses at achieving narrowly defined interim objectives with predetermined means), strategic planning looks at the wider picture and is flexible in choice of its means[i].

20th Century Management Thinkers on Strategy and Strategic Planning

Here we look at some of the great thinkers, academics, practitioners, consultants and advisers who have made significant contributions in the field of strategic planning:

The following notes are based on an article by Morgen Witzel, Financial Times, 5th August, 2003, p11:

Henry Mintzberg has been called 'the great management iconoclast' owing to his willingness to attack previously sacred concepts in business and management. His commonsense approach to management issues has earned him a very wide following and he is perhaps best known for his work on business strategy, where he is said to have exposed the gaps between academic concepts of strategy and reality.

Michael Porter, the other main modern-day strategist, adopted a particular focus on organisational and governmental competence and competitiveness and has written several popular books on business strategy; he has also developed a number of often-used tools and techniques, two of which, his 'Five Forces' and 'Value Chain' models are described later in this module.

The following Notes are based on texts within “Managing Change”, Bernard Burns, 2004, Chapters 6 & 7:

Igor Ansoff is another acknowledged contributor to the development of thinking and practice on business strategy. Regarded by many as one of the pioneers of strategic planning, he was a strong proponent of the 'Planning' school of thinkers. His book 'Corporate Strategy' published in 1965 focused largely on the external, rather than internal, concerns of organisations, including the matching of products to different types of markets - for the analysis of which Ansoff introduced his well known Matrix (Ansoff's Matrix), another strategic planning tool that is still widely used today.

Do we need a formal strategic plan?

There is more than one format, but all strategic planning needs to go through a systematic process to determine if a formal plan is required.

Choices have to be made based on a rationale and on information, and a procedure or planning method has to be followed. Beyond making decisions, 'strategic planning' can and should be used to interact with internal and external stakeholders, building understanding and commitment.

Depending on the circumstances 'strategic planning' can take one day or several months. The time period reflected in the plan varies, although most authors seem to agree on a time horizon of 3 years or more. The following sections detail all steps of a strategic plan.

Any formal planning exercise requires time and resources; resources can be in terms of money or staff time and there should be an understanding of the opportunity costs involved as well as real costs. The timing needs therefore to be appropriate and the resources mobilised proportional to the task and intended outcome. Strategic planning is important whether the organisation's direction needs reviewing, whether its priorities have changed or whether the means of achieving desired objectives need to be updated due to internal or external forces effecting delivery.

The first consideration is to determine whether:

- there are core issues or questions that the strategic planning needs to address

- the timing is right

- the level of resources required are available

In other words do we need to develop a strategic plan or is the one that is currently in place still appropriate?

If the answer is Yes, then the next step is to set in motion the processes for developing the strategic plan and determine 'early stage' roles:

- identify key stakeholders to support the planning process, for example chief executives, department heads, mid-level managers, other internal and external stakeholders, as well as available and necessary sources of information.

- work with key stakeholders to develop a formal work plan to support the planning process

- where appropriate set up task forces on specific aspects as these can save time, spread the workload and can provide high quality inputs.

The Classic 4-Step Approach to Strategic Planning

Here we introduce a very useful structured approach to strategic and change management planning, which was developed from work done initially by Price Waterhouse (accountants) in the 1980s.

The 4-Step approach is a simple structure that helps us to look both holistically and in detail at the drafting and development as well as the implementation of our Plan:

- STEP 1: Where are we now?

- STEP 2: Where do we want to get to?

- STEP 3: How are we going to get there?

- STEP 4: How will we know when we have got there?

STEP 1: Where are we now? - Situation analysis

In this stage we establish our present position – what we sometimes refer to as our “current reality”. This should be an honest and realistic assessment of our position across key factors in the organisation generally and in our part of theorganisation specifically; any ducking of issues or avoidance of existing problems here will have a detrimental impact later.

The context of the strategic plan (new, update, far-reaching changes) will decide which of the following elements to include. Too much information can cause 'paralysis by analysis', equally too little can result in mistakes.

An organisational audit provides objective data about an organisation's set-up, its performance and its problem areas. Components are:

- Organisational history is important, events such as its founding, mergers or dissolutions, changes in senior staff, start or end of main programmes on a time line. It is important to capture this information as it will help the

planning process as it will help to understand organisational culture and how the organisation was set up. - Organisational profile is a stock-take on all current programmes, grouped as appropriate by outcomes or beneficiaries, with indication of coverage, costs, and revenue used. The profile includes, as well information on operation, support

functions such as human resources, finances, and governance (board, management team,). This is important as it will help to provide a baseline of resources currently utilised and those that might be channelled into new work. - Previous and current strategies are the main approaches the organisation has chosen when allocating resources and identifying objectives. It is important as it shows where the organisation has concentrated its efforts in the past and

what investment the organisation has used to reach its position? - Financial assessment is important to establish the stability or volatility of the organisation and to consider previous trends in revenue and expenditure. The organisation will need to consider how much ability it has to move

resources from current programmes to invest in the new strategy. - Governance structure assessment is important as this will support the success or failure of the strategic plan. This will include both formal Governance of the organisation as well as all resources required.

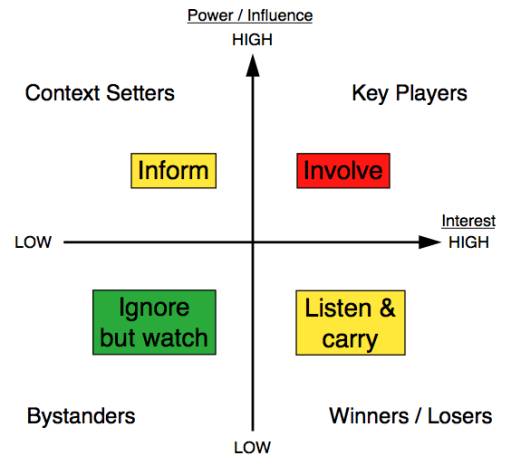

Stakeholders are people or organisations who either a) stand to be affected by the programme/project or b) could 'make' or 'break' the programme/project's success. Workshops, focus group discussions or individual interviews can be used to allow participation in the planning process. It is advisable to engage stakeholders from the beginning of the strategic planning process to get their views and also to obtain buy-in for the new strategic thinking and the forward planning process.

Stakeholder analysis is the identification of a project's key stakeholders, an assessment of their interests in the strategic planning and the ways in which these may affect a project.

The reason for doing a stakeholder analysis is to help identify:

- which individuals or organisations to include in your planning process

- what roles they should play and at what stage

- who you should build relationships with and how you might nurture those relationships

The matrix below outlines how to prioritise stakeholders and make decisions about their importance within the planning process.

Sally Markwell, adapted from:

Mendelow's matrix: See http://kfknowledgebank.kaplan.co.uk/KFKB/Wiki%20Pages/Mendelow%27s%20matrix.aspx

PESTELI trends analysis. The external environment can be further assessed by breaking it down into what is happening at Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, Legal and Industry level, which may be of relevance to the organisation.

Benchmarking is a procedure whereby an organisation compares its own performance in specific areas with the performance of peer institutions. In England the Atlas of Variation is a helpful tool, see https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/atlas-of-variation this compares unwarranted variation in health care expenditure across England. Other examples would include the Cancer Registries data which is collected across Europe. http://www.euro.who.int/en/data-and-evidence/interactive-atlases

SWOT analysis is a widely used tool to formally analyse the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats. Selected staff stakeholders share ideas to complete the following table:

|

Internal forces |

External forces |

|

Strengths: What are we good at? |

Opportunities: Anything happening outside which might actually benefit us if we take advantage of it? |

|

Weaknesses: What do we need to get a grip on? |

Threats: Anything happening outside which we need to be able to defend ourselves from? |

SWOT is a powerful tool when correctly used. It generates long and useless lists when it is not used correctly. Taking into account the purpose of the organisation, critically identify the strengths of the organisation in the recent past, what has definitely been unsatisfactory; and then look at the external environment to recognise which changes could actually benefit the organisation; and which risks the organisation needs to prepare for.

At the end of the situation analysis, there should be a consensus on how much the organisation has accomplished what it set out to do, and how it fares in terms of financial, administrative and governance capacity.

STEP 2: Where do we want to get to? - Future direction

This effectively is our Vision. In a large organisation, such as the NHS, there will almost certainly be an overall Vision, often described in a Strategic Plan and supporting documents. It is also necessary to consider the local situation – within the overall plan what do we have to achieve in our area? Where do we need to get to?

This is summarised by the following statements:

Mission Statement is an organisation's 'raison d'etre' (reason for being). Typically it is expressed in the form of a formal published Mission Statement, designed to provide a sense of purpose to employees and other key stakeholders. The mission will outline the organisation's purpose and values. :

Vision defines the desired or intended future state of a specific organisation or enterprise in terms of its fundamental objective and/or strategic direction, i.e. it is a concise model description of what the organisation's environment would look like if the purpose elaborated above were achieved. Mission and vision, along with a consensus on the organisation's value system (of both organisation and staff) are necessary to convey a clear image of the organisation to the outside world, and to allow staff buy-in.

An increasing number of organisations also draw attention to their core Values and Beliefs that are shared among the stakeholders (including employees) of an organisation. Values typically drive an organisation's culture and influence their priority-setting.

Aims and Objectives

Aims are typically quite broad and will give an anticipated outcome that is intended or that guides your planned actions.

Objectives are the detailed requirements to achieve the overall aim, they are statements of overall desirable achievements, described where possible in quality, quantity, time (e.g., average life expectancy of Londoners increased by at least 2 years for males and females over the next three to five years). Objectives provide definition and direction to the long-term aims and goals that an organisation seeks to realise/achieve and should meet the SMART test: they should be: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound.

STEP 3: How are we going to get there? - Strategy development

This is especially important; it is our carefully thought-through 'Route Map' to get us from where we are now to our vision for the Future. It will comprise a series of detailed actions and steps that we will take to help us to get to “where we want to go”. A core team should be tasked with putting down on paper all the elements of the plan. Any format is fine, as long as it contains:

- An introduction with comments on the process and the team involved/resources used

- Overarching goals and supporting core strategies, along with a rationale for their choice

- Programme portfolio and implementation chronology. Each programme is described in terms of objectives, process, output/outcomes, activities and resources required. A Gantt chart is useful, either for individual programmes or for the whole

portfolio, depending on complexity. Where possible, officers in charge should be identified. - Risks management strategy

- Monitoring and Evaluation framework

- Overall and programme budget, as appropriate.

Making explicit choices on the main approaches to be used over the next few years (core strategies), what is going to be implemented (the overall programme portfolio), and what financial, administrative and governance support will be required.

This entails deciding which programmes to grow, to maintain, or to end. Choices need to be made against explicit criteria, and making best use of the previous analysis. As a guide to decide which programmes to either grow/start, maintain, or terminate, the following matrix can be used (Ansoff[v]):

|

Current Program |

New Program |

|

|

Current Users |

More of the same |

Innovation for current users |

|

New Users |

Increase coverage |

New programme for new users |

The matrix allows making the underlying strategy for a particular choice explicit, while bringing to the attention issues of resources required and risks to be managed.

A formal project plan should be developed to support the planning process and consideration give to setting up task on specific aspects spread the workload, and provide high quality inputs.

There are many different types of Health Assessments that should be taken into account when developing strategic plans, a few are described below:

- Health needs assessment (HNA) “is a systematic method for reviewing the health issues facing a population, leading to agreed priorities and resource allocation that will improve health and reduce inequalities”[vi].

- Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) is a process that identifies current and future health and wellbeing needs in light of existing services, and informs future service planning taking into account evidence of effectiveness at a population, rather than individual level. JSNA identifies “the big picture” in terms of the health and wellbeing needs and inequalities of a local population, it is an essential tool for commissioners to inform joint service planning and commissioning strategies in the Local Authority and the PCT. For the purpose of JSNA, a clear distinction should be made between individual and population need[vii].

Health Impact Assessment is defined by the World Health Organisation, as “a combination of methods, procedures, and tools by which a policy, programme or project may be judged as to its potential effects on the health of population

and the distribution of those effects within the population”[viii]. It usually assesses the impact on health of policies of sectors, such as housing, urban development, transport, agriculture, or environment. HIA aims to:

- Outline the potential positive and negative health and well-being impacts of a project or proposal on a defined community.

- Indicate ways in which any negative impacts could be minimised and any potential positive impacts enhanced.

It involves several steps:

- Draw up a community profile based on statistics and information about the local population.

- Examine published literature about health impacts.

- Examine the policy concerned in relation to the community profile and the published literature.

- Hold workshops and focus groups to find Unearth the views of the stakeholders.

- Summarise all of this information to identify:

- The potential health impacts.

- Suggestions for minimizing any negative health impacts.

- Suggestions for making the most of positive health impacts.

- Consider inequalities relating to any potential impact.

Force Field Analysis relies on the principle that an organisation is not static, but dynamic, and that its current position is a result of the balance between opposing forces. Force field analysis is a management technique developed by Kurt Lewin, a pioneer in the field of social sciences, for diagnosing situations. It is useful when looking at the variables involved in planning and implementing a change programme and of use in team building projects, when attempting to overcome resistance to change.

Change can be either driven or restrained by forces, i.e. persons, habits, customs, attitudes. In a planning session, this can be visualised by a Force Field Diagram. Using three columns, list planned change in the middle column, the driving forces

in the left one, the opposing forces in the right one. Check whether the forces listed are appropriate and whether they can they be changed. Decide which ones are critical, and allocate a score to each (from 1 being extremely weak to 10 being

extremely strong). Decide as well whether any of the forces are actually amenable to change. Now, progress can occur if an opposing force can be reduced, and/or if a driving force can be strengthened. A force field analysis, if well carried out, will reveal opponents and allies, and suggest possible corrective action.

It is inevitable that a number of possible programmes will not be implemented – trying to do everything is no strategy. To decide which programmes to keep, a number of methods for option appraisal and decision-making exist, described in the health economics module (see Health Economics Module).

Cost minimisation Analysis

Cost Effectiveness Analysis

Cost Utility Analysis

Cost Benefit Analysis

Other assessments are risk analysis, and formal project appraisal. At the very least, a set of criteria (needs, capacity, funding opportunities, etc) against which the programme will be reviewed should be set.

Once strategies are agreed and the scope and level of activities decided, it will become apparent what kind of support will be needed. Funding and staffing levels, financial and administrative management systems, external communication, and overall governance of the organisation.

STEP 4: How will we know when we have got there? Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E)

This stage of the planning has to do with key measuring and monitoring aspects. Once we have our journey plan, our Strategic Plan we need to set monitoring points (often referred to as 'milestones' to check how things are going, assess how well or otherwise we are performing against Plan. Thus we schedule key review points as part of a PLAN: ACTION : REVIEW approach. To ensure that we do this effectively we need to determine at the outset a number of relevant Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), these will be critically important areas that we will monitor, measure and assess as we roll-out our Plan.

Monitoring and evaluation links strategy to implementation. It is a structured approach to continuously keeping track of progress using a number of measures identified as being reliable instruments.

Monitoring is an ongoing analysis of whether planned results are being achieved, so that timely corrective action can be taken. Data on specified indicators are systematically collected to inform management and the main stakeholders on

progress in achieving results and in using allocated funds. Inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts of services are regularly analysed according to an established monitoring framework[x].

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model verifies on a small scale if a change or a set of changes actually produces results. Specifying a measurable aim, a time frame and a target population, a small-scale test of an improvement is carried out, the results analysed and those changes that appear successful are refined until agreement is reached on which changes have produced the expected result.

Three questions guide the setup of the PDSA cycle, e.g.

- What are we trying to accomplish? Setting Aims

- How will we know that a change is an improvement? Establishing Measures

- What changes can we make that will result in improvement? Selecting Changes

After which changes can be planned, implemented, their results observed, and conclusions reached as to the possibility of their wider application. Usually a series of cycles is required.

Evaluation is an assessment, as systematic and objective as possible, of an ongoing or completed project, programme or policy, its design, implementation and results. The aim is to determine the relevance and fulfillment of objectives, efficiency, effectiveness, impact and sustainability. An evaluation should provide information that is credible and useful, enabling the incorporation of lessons learned into the decision-making process[xi]. As this is an expensive process, judgement needs to be applied as to whether a particular service or intervention warrants a full evaluation.

Monitoring and evaluation can only be successful if considered at the beginning of a strategic planning cycle so that baseline data for each indicator has been collected and success can be monitored against these data. Indicators are most useful when described in measurable terms, ideally as QQT format (quantity, quality, time). Timing of reviews should be indicated.

Summary

Strategic Planning is, an acknowledged essential discipline, a vital, systematic and ongoing process that enables organisations to plan the use and application of their resources, skills, and knowledge in order to achieve their organisational missions, goals and objectives in environments of ongoing change.

It is especially in times of high levels of change that strategic planning places an organisation in a more agile state, a stated of 'preparedness', more attuned to market and other external conditions and therefore the better prepared to flex or even substantially change their strategic thrusts and operational plans at local as well as at higher levels when fundamental, sometimes structural economic, political and social change occurs.

References

- [i] http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/

- [ii] http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Secondarycare/

- [iii] http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/

- [iv] Ashridge Mission Model, in Andrew Campbell and Sally Yeung, Creating a

Sense of Mission, Long Range Planning, Vol.24, No.4, pp10-20, 1991 - [v] Richard Koch, The Financial Times Guide to Strategy, FT Prentice Hall, 3rd edition 2006

- [vi] http://www.nice.org.uk/aboutnice/whoweare

- [vii]http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/

- [viii] WHO European Centre for Health Policy and WHO Regional Office for Europes; see as well http://www.liv.ac.uk/ihia/, and http://www.who.int/hia/en/

- [ix] Public Health Resource Unit (PHRU), at http://www.phru.org.uk/~casp/

- [x] OECD – 2002b (Focus newsletter #13)

- [xi] European Commission, Project Cycle Management Guidelines, at http://ec.europa.eu/

(Authored with Jurgen C Schmidt and Martyn Laycock)

© JC Schmidt, K Enock, M Laycock 2009, C Beynon 2017